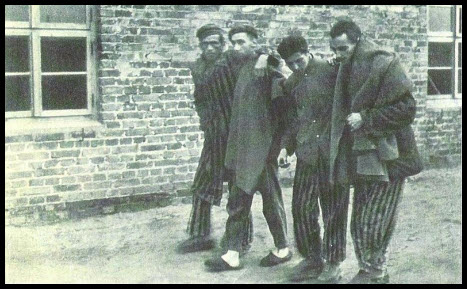

Holocaust survivor George Salton (second from right), on the day of his liberation from the Wöbbelin concentration camp by U.S. soldiers on May 2, 1945.

Few among us can ever claim to have been living witnesses to the existence of hell. But Dante, the famed poet of the three-part Divine Comedy, and my late grandfather, George Salton, stand as sacred examples.

“You living one,” warns the demonic riverboat carrier named Charon to Dante at the underworld’s watery mouth to hell in part 1 of the Divine Comedy, the Inferno, “this route is for the dead.” In the Inferno, Dante visits hell under the protection of heaven and with the escort of the poetic guide Virgil. For my grandfather, George Salton, in his descent into the Holocaust, there were no such assurances available.

Innocent in Hell was the original working title my grandfather had conceived of for his written Holocaust account. “While the story in the book is told against the overwhelming background of the Holocaust,” he writes in what would later become the afterword to The 23rd Psalm: A Holocaust Memoir, “it is rather the story of a young boy and his descent from the happiness and innocence of childhood…into the shadows of the pit of horror where nothing but survival mattered.”

In his unbearable, infernal Holocaust waking nightmare, my grandfather soon has only his brother Manek to turn to, “my guide and my protector,” when his parents face their untimely doom in the gas chambers. “God, dear God, You are all powerful and merciful. Save us,” George prays, as he and Manek are questioned in the Rzeszów ghetto alongside other Jews forced to run, squat, and jump, under the brutal eyes of the Nazis, to demonstrate their fitness as slave laborers. “I wondered if maybe in this place, on this day, prayers did not matter,” George writes. “I was in hell. I had just learned what a selection was.”

My grandfather then has no one he knows with him through the trials of 10 concentration camps. “I was alone in the hell of Płaszów,” he recollects of one camp. Of another, he finds in Dante’s poem a description of what he endures:

“I was entering the gates of hell. I remembered and understood Dante’s words in my mother’s [copy of his] book: ‘Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.’ A prisoner mumbled that we were in the concentration camp called Ravensbrück.”

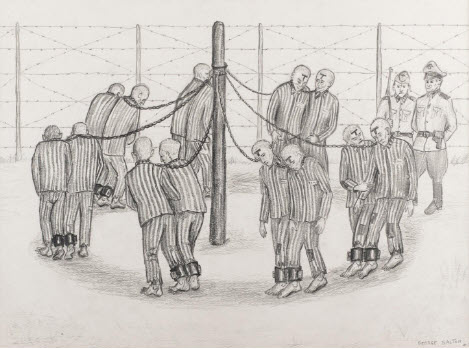

In the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, my grandfather observes the torture of French resistance prisoners who march in endless circles under the weight of heavy irons, condemned to be hung. To my mind, this mercilessly cruel punishment can only be compared to the Eighth Circle of Hell, in Dante’s Inferno, where the souls of the damned loop round and round in burdensome lead clothing, forever.

Pencil sketch by George Salton, depicting the torture of French

resistance prisoners in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, 1944.

There was another Holocaust survivor whose knowledge of Dante in the camps sustained and — according to his own reflections — “perhaps it saved me.” Michael Berenbaum, the renowned Holocaust scholar and one of the creators of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, writes in his foreword to The 23rd Psalm: A Holocaust Memoir, “As I read Salton’s memoir, I kept thinking of another scientist who was engulfed by the Holocaust, Primo Levi, who found himself deported to a concentration camp. He applied his talent for observation much as [George Salton] did.”

Similar to my grandfather’s portrayal of the selection process in The 23rd Psalm, in his memoir Survival in Auschwitz, Levi describes the selection ordeal in Dantesque terms: as those who are fit to work are separated from those sentenced to be gassed, Levi calls the Nazi guard “our Charon” and writes upon his entry into Auschwitz: “This is hell. Today, in our times, hell must be like this.”

Later on in his imprisonment, Levi famously recites a passage from Dante’s Inferno to a fellow camp prisoner. The music of the words themselves; no, even more—the entire weight of his country of Italy’s poetic tradition and the brotherhood among all those who suffer come to life through Dante’s poem. This is what poetry is for. For a moment, Levi is no longer alone in the hell of Auschwitz; the spirit of Dante has come to his aid, just as the poetic ghost of Virgil had come upon Dante in the time of his troubles.

Tragically, Dante’s poetry would become twisted under the hands of the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and used for the malignant purposes of creating anti-Semitic and fascist propaganda during World War II. Yet, for some of the Italian survivors of the Holocaust, including Primo Levi, Dante’s verses were nevertheless important in helping to express what all they had suffered. For these survivors, the moment of liberation from the concentration camps felt comparable to none other than Dante’s escape from the Inferno of hell and into the wondrous, open air, towards Heaven.

Having survived the Inferno, Dante must then climb the formidable mountain of Purgatorio (Purgatory) in part 2 of the Divine Comedy. Likewise, Holocaust survivors like my grandfather confronted a bitter transition period following the war. “It was for me both a good time and a bad time,” my grandfather writes, as he waited two years in a displaced persons camp before arriving in the United States in 1947. “All the people that loved me were dead…I was alone. I had no education, no means, and I did not speak English.” He would learn English in night school classes, as he worked during the day.

The Eighth Circle of Hell in Dante’s Inferno, Canto 23, where their eternal punishment is to march in endless circles. Siegel, Jane. “Illustrations from Early Printed Editions of the Commedia.” Digital Dante. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2017. https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/image/digitized-images/

At one point, my grandfather had to take an Introductory Poetry Class, in English, as part of the undergraduate coursework he undertook to transition from having only a 5th grade education before the Holocaust to becoming a college graduate. He found himself deeply moved by the material and took notes in the poetry textbook’s margins. But it was one poem in particular my grandfather encountered after the war that made him tremble to his core: Psalm 23. According to my grandfather, as a Holocaust survivor, “I [had] lived the words of David’s psalm: ‘Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for Thou art with me.’”

He would choose The 23rd Psalm for the title of his book, because “I felt that David, who wrote the psalm, must also have gone through some terrible experience. I wanted to acknowledge the psalm had special emotional meaning for me.”

The Psalms of David also play a centrally significant role in Dante’s Divine Comedy. Early on in his poem, when he is caught in the grip of traumatic fear, Dante’s first spoken words to Virgil come from Psalm 51: “Have mercy on me!” David himself is redeemed as “the highest singer of the Highest Lord” to earn a place in Dante’s Heavenly Paradise, where he is specifically celebrated as the author of Psalm 51.

One passage especially crystallizes the relationship between David and Dante in the Comedy. In Canto 25, of part 3 of the Divine Comedy known as Paradiso (Paradise), Dante is questioned by St. James on the meaning and value of hope. “Hope,” Dante responds, “is the certain expectation of future glory.” Dante further explains that he first learned of having hope in God by reading the Psalms of David, and that from here on forward, Dante’s own mission will be to share the lessons of hope he has learned with others who need it.

Unlike Dante, whose hope was a certain expectation of glory, my grandfather’s hope led to an experience of glory that was unexpected and miraculous. “Dear merciful God of my people Israel,” George prays in words that echo David’s Psalm 51 as the Nazis fired from the towers in the 10th and final concentration camp, “Blessed be your name. Forgive me my sins. I know I have had doubts and questions, but I still have faith in you. You are my staff and my salvation. Have mercy on me, God.” Minutes later, my grandfather joins the crowd of joyous prisoners to celebrate the arrival of his American liberators. “We told each other that we had survived and that we should never have given up hope. This was our day of glory.”

Having been through the valley of the shadow of death, in David’s words, my grandfather once reflected after a gathering of Holocaust survivors in language that resonates with Dante’s imagery: “It was a mountain of strength…that we who have gone through this hell had the resilience, had the faith, had the hope to have families [and] look to the future.”

Just as Dante’s medieval masterpiece was a story for all people, throughout all ages, of all faiths, on the merits and value of hope, so too does my grandfather close The 23rd Psalm with these words about Holocaust survivors: “And if somebody, any person, has had some difficult and troublesome and frightening experience and looks for some lessons of hope, look to us.”

May the words of these poets who journeyed to hell and back remind us to keep hope alive in our times of ruin and of triumph.